1941年12月8日、日本が東南アジア各地とハワイで英米軍に対して同時多発攻撃を行って始まった3年8カ月のアジア太平洋戦争。この記念日特集として、昨年戦後70周年記念としてバンクーバーで開催した高嶋伸欣氏(琉球大学名誉教授)の講演(2015年10月17日)「和解に向けて―アジア太平洋戦争終結70周年記念講演ー」の英語訳を紹介します。日本語版はこちらをクリックしてください。

To mark the 75th anniversary of the December 7/8 (depending on the time zones), 1941 Imperial Japan's simultaneous attacks against British and American colonies and bases throughout the Asia-Pacific, which started the 3 years and 8 months of Japanese war against Allied Nations, Peace Philosophy Centre presents an English version of the talk by Professor Nobuyoshi Takashima, Emeritus Professor of the University of Ryukyus, which was held in Vancouver, BC, Canada on October 17, 2015, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the ending of the Japanese wars of the Asia-Pacific. Professor Takashima has spent the last four decades trying to teach the public that the nature of the Japanese war against Allied nations that started on December 7/8, 1941 was Japan's invasion into Southeast Asian countries for their rich resources, such as the oil of Indonesia (then Dutch East Indies) and iron ores of Malay Peninsula (then British Malaya) in order to continue their invasaion and war against China that had been going on since 1931. He has been leading study tours to Malaysia and Singapore to learn and teach about the massacres of people of Chinese decent by the Japanese Army during the war.

We all know Japanese Navy's attack of US Navy base at Pearl Harbor, but how many of us know that Japanese Army's attack on Kota Bharu, Malaysia against the British Army happened more than an hour before Pearl Harbor? Here is the timeline of the day (December 8, by the Japanese time zone).

Kota Bahru, Malaysia: 02:15

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii: 03:20

Landing of 5th Division into Thai territory of Malay Peninsula: 04:12

Bombing of Seletar Military Port, Singapore: 05:38

Bombing of Hong Kong: 08:00

Bombing of Guam: 08:30

Bombing of Wake Island: 10:10

Bombing of Clark Airfield, the Philippines: 13:32

(Source: Kihata Yoichi, Sasaki Ryuji, Takashima Nobuyoshi, Fukazawa

Yasuhiro, Yamazaki Gen, Yamada Akira, Document: Shinju wan no hi (Document: The Day of Pearl Harbor), Otsuki Shoten, 1991)

Overemphasis on the memory of Pearl Harbor obscures the true nature and significance of Japanese wars of the Asia-Pacific. It was not a Japan-U.S. war. It was not just the United States that won the war. It was the anti-imperialist resistance and resilience of people of China and all the other Asia-Pacific countries that were colonized and invaded by Japan and the military forces of the Allied Nations that defeated the Japanese Empire.

Later this month, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is set to visit Pearl Harbor to stage another political performance with the U.S. President Barack Obama to show off the U.S.-Japan military alliance, just as they did when Mr. Obama came to Hiroshima on May 27 this year. We should not let the two leaders, particularly Mr. Abe who is known for denial of Japan's aggressive past, get away with preying on the memory of the war in which hundreds of millions of people of Asia and hundreds of thousands of Allies' POWs were victimized by the Japanese Empire's colonial rule and military aggression, for their political advantage.

Here is Professor Nobuyoshi Takashima’s talk.

Satoko Oka Norimatsu, December 8, 2016

Toward

Reconciliation: The 70th Anniversary of the end of the Second World

War in the Asia-Pacific

October 17, 2015 at the Unitarian Church of Vancouver

(BC, Canada)

Translated

by Koki Norimatsu, with the assistance of Satoko Oka Norimatsu

|

| Nobuyoshi Takashima and Satoko Oka Norimatsu as his interpreter. October 17, 2015. Photo by BC ALPHA |

My name is

Nobuyoshi Takashima. I came to Vancouver for the first time. I am glad to meet

you.

The initial

motive for me to visit Vancouver was to better understand the history of my

father (Nobutaro Takashima), who was the first principal of Steveston Japanese

School.

The

Japanese passport with which he came here back then was preserved in my older

brother’s house. According to its records, the year in which my father arrived here

was 104 years ago, in 1911.

He worked

as a teacher here for ten years, and returned to Japan in 1921.

I have

several memories of my father’s students, who received his instruction during those

ten years, visiting my father in Japan after the war.

I have

always wanted to visit Vancouver once for these personal reasons, so I am very

grateful that Ms. Satoko Norimatsu, and the members of VSA9 here have planned

this event, and given me this opportunity to speak to you.

The members

of VSA9 all act under the belief that Japan must never return to its pre-war

militarism. Thus, as one who has been researching Japanese atrocities in

Southeast Asia for many years, I felt it would be appropriate for me to share

my findings at a gathering such as this one.

The main

focus of my research is to uncover the fact that during the war, the Japanese

army had specifically targeted and killed those living in Southeast Asia, who

were either Chinese or of Chinese descent.

To the

families of those who have suffered, I am a Japanese—a member of the assailant

nation. They were puzzled as to why I would be conducting such research, and

were suspicious of my motives.

Initially I

was visiting the sites of these atrocities alone. As a result I was told, for

example, “Japanese shouldn’t come to places like this. Why are you here?”

People there also yelled at me, almost hit me, throw stones at me, and

protested against me for hours. I had many of such experiences.

Still,

there was always somebody among the local Chinese people who would defend me,

and explain that not all Japanese people were the same—that there were some

like me too.

As a school

teacher, I want to teach my students the truths of the invasions conducted, and

the atrocities committed by the Japanese army during the war. As a means to do

this I have come to inquire the people of Asia of such truths. I explained as

such to them several times, and after repeated visits, the locals gradually

understood me. Several of these local people showed their support, and offered

to assist me in my search by collecting information.

Thanks to

their support, I can now organize tours with others—mostly like-minded teachers—to

Malaysia without the worry of conflicts. The local people would cooperate by

explaining things and gathering information for us, and this is how this

endeavour has sustained up to now.

As I

reflect, I truly feel that my activities in Asia have only been made possible with

the trust and understanding that have been accumulated with the help of the

locals. Recently, as I grow old, there have even been several younger educators

and scholars who say they are willing to succeed my work.

The first

time I travelled to Malaysia was 1975. This means I have been continuing this

process for forty one years.

|

| Nanyang Siang Pau, March 4,1999 |

This is an

image of the feature article published on the Nanyang Siang Pau, a Chinese-language

paper in Malaysia, on the date March 4th 1999.

This was

when the Japanese government made clear its position to legislate the Hinomaru—the Rising Sun Flag as the

national flag, and Kimigayo as the

national anthem. When the position of the Japanese government was announced,

this article was immediately published on this paper.

To the

Chinese people of Malaysia the Hinomaru and its variant, the ensign of the

Japanese Army, are reminders of a harsh past. They could not approve of the

fact that the flag was becoming the official national flag.

Those countries which have been invaded by the Japanese believe strongly

that Japan’s responsibility upon defeat was to properly own up to its

wrongdoings. However the reality was quite on the contrary; the one with the heaviest

responsibility of all, Emperor Hirohito, and his wife, the Empress, both

fulfilled their lifespans unpunished. To the people of Asia, the Hinomaru is a

deep reminder of this irresponsibility in Japanese society.

The headline of this article makes this position clear. It emphasized

that Japanese militarism has not been abolished, and the establishment of the

Hinomaru and Kimigayo as national symbols has proven this.

What is

further worth noting is the following image of Yasukuni Shrine.

The fact

that the Emperor Hirohito was unpunished, the existence of Yasukuni Shrine, and

the Hinomaru form a trinity which together, to the people of Asia, symbolize

Japan’s unwillingness to take responsibility for its wrongdoings during the war.

This incident proved to us that every time something like this [legislation of

the national flag and anthem] happens, it will immediately be published in this

way.

This

article was published in 1999. Even after 25 years of our investigations in

Asia, such articles are still appearing. We were made to acknowledge once

again, that as Japanese citizens, it is our responsibility to further pursue

the truths of Japanese invasions during the war.

|

| Lianhe Zaobao, May 25, 1990 |

Again, this

is a Southeast Asian newspaper article. This is a Chinese Singaporean

newspaper, Lianhe Zaobao, May 25, 1990.

This was in

1990, ten years before the previous article. The main headline outlines a

speech made by Lee Kuan Yew, the Prime Minister of Singapore at the time.

He predicts

here that soon a time will come when the post-war generation of Japanese people

will claim political power in Japan. He continues to say that when that

happens, that post-war generation of politicians will abandon its security

treaty with the United States, independently develop its own military, and

become a military power with its own nuclear weapons.

Aside from

a short period in which the opposition held power, the conservative Liberal

Democratic Party has been in power for the vast majority of Japan’s post-war

years.

For us, this conservative party [LDP] held dangerous ideologies. That

being said, the leaders of the party were from the generation which had

experienced the wartime. As a result, their position against Japan’s pre-war

militarism was one they shared with their oppositions.

However these leaders of the conservative

party retire with age. They will inevitably be replaced by the following,

post-war generation of Japanese. Once this happens, it can never be said for

sure what these new leaders will do, considering their lack of war experience.

This is what Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was predicting.

You may know already from watching the

news, but currently Japan is rapidly undergoing a dangerous transition to

militarism under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Abe was of course born after the war, just

as his predecessors Koizumi and Fukuda were. We are again forced to learn from

these kinds of newspaper articles, that Japan’s current situation is in fact

exactly as Lee Kuan Yew foretold.

In this situation, we have been conducting

research in Southeast Asia on the Japanese army’s invasions, and the entailing

mass murder of civilians, with the support of many others. This means that our

efforts are clearly in opposition with the political stance of Prime Minister

Shinzo Abe and his party.

Inevitably, our efforts have repeatedly met

interference from the government, conservatives with similar ideologies as Abe,

and Japanese right-wingers. On the other hand, there are many who also support

us both in Japan and in Southeast Asia, and thanks to them we are able to

continue our activities.

Now I stand here, speaking of our work to

people of Vancouver, Canada. Canada’s relevance to this matter has also been

proposed here, as Canada was one of the countries which signed the San

Francisco Peace treaty—a treaty that acquitted Japan of its war crimes. I hope

my talk will give everybody here some material to think about and I am very

grateful for this opportunity.

|

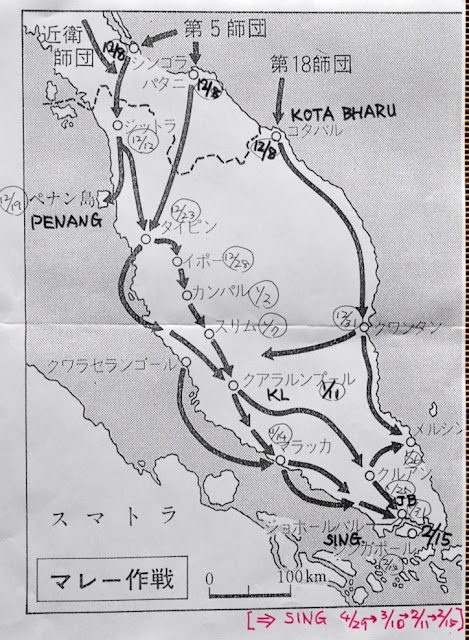

| Japanese Army's invasion routes through Malay Peninsula, December 8, 1941 to February 15, 1942 |

Finally, let’s get into the specifics of

what exactly we have been doing in Southeast Asia, and what exactly we have

discovered. This map, although it may be difficult to see, is a map showing

Japan’s course of advancement from the Malay Peninsula into Singapore.

The Japanese army’s primary target upon

landing on Malaya was the invasion of Singapore. This map shows how the

Japanese military fought the British forces through Malay Peninsula.

If you look at the northern part of the

east coast of this map, it says Kota Bharu. It’s where the third arrow is. The

date recorded is December 8th. During the early morning of this day, the

British forces stationed at a base in Kota Bharu clashed with the invading

Japanese Army. What we call the Asia-Pacific War began here.

Many history books state that the Asia-Pacific

War began with the Japanese bombing on Pearl Harbor. However, the battle in Kota

Bharu began over an hour before Pearl Harbor. This is a fact recognized by the

majority of historians today.

However, the large majority of Japanese

journalists, mass media, and politicians disregard this fact, and repeatedly

claim that Pearl Harbor was the beginning of the Asia-Pacific War.

The Japanese army’s true aim upon invading

the Malay Peninsula was to claim the lands’ resources—iron ores from the Malay,

and fossil fuels from the neighbouring Sumatera. It can be analyzed that the

claims of Japanese media and politicians mentioned above, are made to obscure

this fact to the public.

We have presented documents such as these

to textbooks writers to prove that Kota Bharu was in fact already a battlefield

over an hour before Pearl Harbor, and demanded multiple times for this fact to

be entered in future editions of history textbooks.

As a result, current middle/high school

history textbooks are increasingly changing their contents, to say that the war

began from Kota Bharu.

That being said, this change alone took

approximately thirty years to realize. In addition to this, the mass media’s

position on historical revisionism is unwavering, and they continue to tell the

public that Pearl Harbor ignited the Asia-Pacific War.

This year, as December 8th

approaches, we will be attentively watching to see how the Japanese mass media

take up this issue. I hope that you will also do the same here in Canada.

It took thirty years for the origins of the

war to be accurately listed in the textbooks, so naturally it took even longer

for further details of the invasion of Southeast Asia to be properly mentioned.

|

| A high school history textbook from 1980s |

This (right) is a high school textbook from the

1980s. Among the approximately ten textbooks that were commonly used at the

time, this particular one was the most popular, dominating fifty percent of the

shares. Yet, somehow it could only spare the underlined area—about two measly

lines—to mention the invasion of Southeast Asia.

|

| Recent junior high school textbooks in Japan |

These are four excerpts from the most

recent versions of middle school history textbooks. It says that in Singapore,

the Japanese army massacred approximately 35,000 civilians. The bones of these

victims were excavated from around the island, reburied in one location, and a

memorial was built upon them. This all happened in 1967. This is a photograph

of this memorial—this, and this here too. So it can be seen that these

textbooks give detailed descriptions of atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese

army along with photographs.

There’s another one here so that makes four

photographs. This fact is noted in four different textbooks.

As I previously explained, the mass murder

of civilians by the Japanese army is now a properly written fact in textbooks.

This means that this incident is now officially acknowledged as a truth by the

Japanese ministry of education through textbook screening.

|

| Jinchu-Nisshi by 11th Infantry Regiment, 5th Division of Japanese Army, March 1942 |

This is a Jinchuu-Nisshi, an official record of

Japan’s military, and the unmoving proof of the massacres of civilians by the

Japanese army. Each unit was instructed to keep a detailed record of what happened

that day, and what they did on that day. In October of 1987, we discovered this

one being preserved within Japan, and it was made widely public through the

mass media in December of that year.

This

particular example here is from a unit which committed the massacre of

civilians in the state of Negeri Sembilan, located inland of the Malay

Peninsula. Such official order of massacre was issued to different army units.

It was the order for execution of so-called “hunting of enemy Chinese.” The

order was as follows: to target and kill anybody of Chinese descent considered

to be in opposition of the Japanese army, regardless of their gender or

age.

Upon

accepting the Potsdam declaration, the Japanese Army Headquarters required that

all such records of the battle be burned and destroyed. As a result the

majority of these documents of other units are yet to be found.

On the

other hand, this 11th Regiment of the 5th Army Division from Hiroshima

made a mistake and its 1st and 2nd Battalions, including

the 7th Company [which recorded the massacre in its Jinchu-Nisshi],

were captured by US forces before Japan surrendered. Their documents were

confiscated by the US military before they got a chance to burn them, and were

later returned to the Japanese government after being used as evidence in a war

crime trial, and then preserved until we discovered them.

|

| Jinchu-Nisshi where facts of massacre are recorded |

I apologize

for the small font size, but this is an excerpt from the Jinchuu Nisshi of

March 1942. Under the entry of March 4th, this unit [7th

Company] credits itself for bayonetting and killing fifty five “enemy Chinese. “

Now as we

proceed to March 6th, here it says again that this unit bayonetted to

death a hundred and fifty six more.

As you can

see, the Japanese Army had advanced throughout the Malay Peninsula, bayonetting

any Chinese civilians, children or elderly, women or men, on the spot without investigation

or trial, or even a record of their identity. This happened on a daily basis.

These

operations violated The Hague Land War Convention, which at the time Japan had

already signed and ratified.

This

international law, while accepting the inevitability of soldiers killing

enemies in action, required that any prisoners of war without the will to fight

must have their rights ensured. While those conducting military activities

without a uniform are considered spies and do not receive the same treatment as

said prisoners, the law still secures their rights to be properly tried. This

applies even if the defendant is captured in action and it is clear that he/she

is a spy. The Land War Convention asserts that the defendant must not be killed

unless put under a trial, and properly judged into the death sentence.

Despite

this law, the Japanese military had sent official orders to its units on the

field, authorizing them to kill civilians according to their own judgement.

The

massacre of Malaysian civilians on its own is proof that the Japanese Army had

been waging a despicable war, which completely disregarded international law.

We also know today that such downright violations of law were performed also throughout

the mainland of China. Among the most infamous of such violations is the

Nanking Massacre.

In Nanking,

the decision to kill captive Chinese soldiers was made by the units in the field. Without sufficient food supply

for the prisoners of war, the front-line commanders ordered the soldiers to

kill them. These facts have been discovered now from the diaries and

testimonies by the former soldiers.

Among those

held captive were soldiers who abandoned their uniforms. Although international

law had it that such captives did not receive the treatment of prisoners and

would be treated as spies, they still had to be tried in court.

If the

Japanese military had abided by international law and tried these captives in

court, there would have been records of it. It would have been easy, even

today, to check their numbers and each of their names.

Because the

Japanese military ignored international law and did not go through any kind of

trial, there is no concrete record of exactly how many were killed. So even now

as the Japanese side refutes the history saying that the “300,000 victims” that

the Chinese side claims is “too many” or “a lie,” the Japanese themselves are

unable to prove an accurate number either. The most they can do is give a vague

estimate according to the information available. As of now, this debate on the

number of casualties has continued for over half a century.

You may

know already from the news, that the Japanese government has reacted

hysterically to the Chinese proposal to register documents about Nanking

Massacre with UNESCO Memory of the World. Japan has provoked controversy

against China over this issue.

There is

nothing justifiable about such recent behaviours of the Japanese government, if

you would only look at the series of documents I have shown today. These

behaviours by the Japanese government are truly shameful, as done by Japanese

people, I think.

|

| Shashin zusetsu: Nihon no Shinryaku, Otsuki Shoten, 1992. This map shows memorials to remember Japanese Army's killings of people with Chinese descent across Malaysia. |

Around the

same time that we got our hands on the Jinchuu-Nisshi,

we were also on the search for the graves and memorials of Malaysian victims

with our local friends. What is on the screen is a summary of this endeavour. These

two pages of my book published in 1992, using a map and several photographs,

tell of thirty of such locations.

As you can

see, a huge number of incidents took place within the state of Negeri Sembilan.

As of 1992, we were able to recognize the existence of memorials built for each

of these sites.

At first,

we were really fumbling in the dark to find these places. We would aimlessly

hit the road with our rental car, and if we were lucky enough to come across a

Chinese graveyard, we would search it for any kind of clues. Eventually, as we

were able to gain information from the local people as to where to search, by

1990, we were able to find a lot more of such places.

In 1992,

when we were finally able to publish them in the form of this book, I knew that

I had to return to Malaysia with a copy of these pages and tell them my

gratitude. When I showed them, I learned that the local people had knowledge of

memorials in their area, but had no idea that so many were scattered throughout

Malaysia.

Many young Malaysian journalists felt that,

seeing the Japanese people do such research, they should have done it

themselves. I was pleased by their enthusiasm that they thought now it was

their turn to take the initiative and conduct further research in the areas

that we did not know fully yet.

As a result, the amount of information we could

obtain from the local people of these areas—Northern Johor, the state of Perak,

North of Kuala Lumpur, and the Northeastern region near Kota Bharu—grew

exponentially.

Thanks to them, we have been able to identify

seventy two of such graves and memorials.

Instead of keeping these findings to ourselves,

we always try to tell them as widely as possible every time we reach a

milestone in our research.

Many textbook writers, although they did not

participate in our tours, have begun to use these findings and include them in

their publications. Because the massacres in Malaysia have already been

acknowledged as an official truth, the ministry of education can no longer tell

these writers to cut this content. As of now, the situation allows for

textbooks to have a certain degree of deterrence against historical

revisionism, at least on the topic of Southeast Asia. However this also means

that pressure from the revisionists—including Abe—is increasingly becoming

heavier, both in the form of direct attacks against us, and in efforts to

revise the textbooks.

Still, we cannot succumb to such pressures. We

intend to continue uncovering and proving truths as a means of fighting

historical revisionism.

Next I would like to tell you about a story of

reconciliation that unfolded under such endeavours of ours.

During the war, the Japanese were conducting a

“divide-and-rule” tactics on their occupied land, by deepening the division

between the Chinese and Malay residents. The

policies of ethnic division employed during the war fostered ill will that

remains in Malaysia even today. However in this

story, the increase in awareness of the past massacres led to the

reconciliation of the two ethnic groups.

|

| Memorial in Sungai Lui right after it was discovered |

What you see in this photo is the grave of

massacre victims that was found coincidentally in the jungle over thirty years

ago. Underneath was 368 bodies, which were relocated from the temporary burial

place. Over the years the existence of this grave was forgotten, and vegetation

reclaimed the area. The photograph is from 1984, when it was once again found.

Its location is on the fringes of Negeri

Sembilan, in a small village called Sungai Lui.

Although it was small in quantity, gold was

being found in Sungai Lui at the time. People flocked to get their hands on

this gold, and in front of the train station stood vendors, aiming to reap

their share of the profits. The town was modestly flourishing, when the

Japanese army invaded. It is said to be August 29th of 1942 that the

Japanese rounded up all of the villagers at the train station, and specifically

targeted and killed only those of Chinese descent.

The previous day, a Malay working for the

Japanese military as a spy was killed by a Chinese member of the anti-Japan Guerrillas.

This brash decision—to kill these civilians with little to no trial—by the

Japanese was a form of retaliation. This is also recorded in the Jinchuu-Nisshi that I showed you above.

It is a well-known fact in western society that

similar things have been done by the Nazis in Greece and Yugoslavia, but such

incidents in Asia are often ignored.

What I would like everybody to pay attention is

how the Japanese military had been using Malays as spies to combat the

anti-Japan Guerrillas. They were using them in such a way that would induce in

both groups—Chinese and Malay—a hatred against each other. Even during the

massacre in Sungai Lui, Malay villagers were pushed aside while the Chinese

were being murdered indiscriminately.

Even after this grave was rediscovered, the

split in the demographic made during the war almost ignited another conflict.

If you would take a look at this photograph, the trees around the grave have

been cut clean and the area is brightly lit. This deforested land is the

portion that was sold cheaply by the state government to Malay farmers as

farmland.

The Malay residents of the village felt that

their livelihoods were being endangered by the discovery of this grave—that the

Chinese people were going to claim their farmland for their own. One after

another, Chinese people who caught wind were coming to Sungai Lui to take a

look. Some worried Malay villagers threw stones at the Chinese visitors, and

the village was on the verge of a racial conflict.

To prevent any serious conflict, police

officers were stationed in the village. For a considerable period, it was a

frequent occurrence for Malays and Chinese to nearly clash, and for the police

to have to intervene.

However even with a difference in race and

religion, the Malays understood the significance of a grave to its people.

Eventually they would feel less of a repulsion to losing their land, and came

to a consensus that it wouldn’t hurt to give away a small amount of land around

the grave.

After this process of reconciliation, we as

Japanese are now able to visit a land that we would otherwise be repelled by.

Upon our visit, we were able to know why the Malay villagers changed their

minds. It was Muhyiddin, the Malay mayor of the village

who coordinated the

discussion among the Malay people.

At the time of the massacre, Muhyiddin was sixteen. He happened to be at the train

station and witnessed the scene. He was told to stand aside by the Japanese

soldiers, and watched, trembling with fear, as the Chinese villagers were being

mowed down with Machine guns.

His memory was clear at the age of sixteen. He

told us in tears of the atrocities that unfolded before his eyes.

In the time of conflict between the Chinese and

the Malay, he was the one who convinced his people to give up a small portion

of their farmland. He discussed the matter with the Chinese chief of the village,

Lim, and played a large role in resolving the conflict.

|

| Chinese and Malay mayors attend the memorial ceremony together |

Every August, we have visited Sungai Lui during

our tours and received updates from the Chinese mayor Lin. One year, he told us

ecstatically that the Malays agreed to give away their land. He also said that

he was collecting donations in order to raise money to refurbish the grave and

the land around it, so I asked if we Japanese could donate too. He happily

accepted the offer, so the next year we brought with us 10 thousand ringgits

(approximately 300 thousand Japanese yen) for the village, which we had

collected from people all over Japan.

Thanks to the people of Japan and locals of

Malaysia who donated, and especially Mayor Lin who pulled a lot of money out of

his own pocket, the said grave has now been beautifully refurbished as you can

see in the below photo.

|

| Sungai Lui memorial, after the improvement |

On the other hand, the commander of the

Japanese unit who gave the orders to kill the villagers bore much

responsibility. The previous Jinchuu-Nisshi

had a detailed record of what happened, so he was tried and put to the death

sentence accordingly after the war.

The commander’s name was Second Lieutenant

Tadashi Hashimoto, and the unit he led was from Hiroshima. He was single and

had no wife or children, but had a nephew named Kazumasa Hashimoto. Kazumasa

believed that his uncle’s war crimes cannot be forgotten. Out of a desire to

visit Malaysia once and talk to the victims’ families, he joined us on our

August 2012 tour and visited Sungai Lui. A Malaysian newspaper took this up

too.

|

| From right, Mayor Lim, Mr. Hashimoto, his wife and son |

This (photo) is from this August (2015) when Kazumasa once

again visited Sungai Lui. This time he came to meet Mayor Lin with his wife and

son.

When he first joined us three years ago,

Kazumasa was very worried about the backlash he could get from the locals of Sungai

Lui. Understandable, as he is—after all—a relative of Tadashi Hashimoto.

Against his expectations however, he was greeted by the villagers with open

arms. They appreciated the courage it must have taken to set foot on that land,

and insisted that he would come again. He gladly took up that offer and did

indeed return this August—this time with his family.

|

| Suzuko Numata |

I had previously said that the unit led by

Tadashi Hashimoto was from Hiroshima. I would assume that you also know that

Hiroshima is the city that fell to the atomic bomb—Little Boy. Suzuko Numata, a

woman who lost a leg to this bomb, was against making herself solely a victim

of the atomic bomb.

Upon learning that it was soldiers from Hiroshima that

conducted mass killings of civilians in Malaysia, she decided to take part in

our tour of March 1989. Like Kazumasa, she was kindly greeted by the people of

Malaysia.

This is a photograph from when Suzuko joined us

to the site of the massacre. She gave a speech during a gathering with the

Malaysian people, telling about how she learned three years ago from Takashima

that massacres were conducted by soldiers of Hiroshima, and how she felt a

responsibility to come to Malaysia once and give an apology to the people. We

had the pleasure of being there, as the Chinese locals all stood up to welcome

her speech.

|

| Prime Minister dedicating flowers to the victims of Japanese Army's massacre of people with Chinese descent in Singapore. This was reported in a newspaper in Singapore on August 28, 1994 |

This (above) is a photograph is from

1994, when Prime Minister Murayama visited Singapore a year before his Murayama

Statement—the statement which Prime Minister Abe is keen on denying. Murayama

was the first Japanese prime minister to ever pay his respects to the Civilian

War Memorial in Singapore, and this event was taken up as a significant event

by Singaporean newspapers.

|

| A newspaper article that reports Singapore lending items related to the war-time massacre. July 1990 |

This (above photo) is concerning my own

activities. When the bones of Singaporean

victims were discovered, their belongings that were found along with their

remains were mostly of the same type, and thus were mostly stored away. This is

a newspaper article from when I requested for permission to take some of them

home, so they could be exhibited for the public, and used as teaching material.

They initially declined my request that they could

not lend such objects to the Japanese. Still I persisted every year, and

several years later they accepted, saying that they trusted our sincerity.

This photograph is actually from when we

returned them. Since they told us that they didn’t all need to be returned,

thirty of these articles are still in Japan, and are being shown in classrooms,

and at the Peace Museum of Ritsumeikan University. I have brought with me about

ten of them, so I would appreciate if you would take a look at them later. For

example, these are glasses. Glasses were among the most common belongings found

among the remains, but they very seldom have names written on them and cannot

be returned to the victims’ families.

|

| Takashima at the time of his textbook lawsuit |

These articles were exhibited all around

Japan and were seen by many eyes. It was proven that even in Japan, there were

many who were interested in such matters. With cooperation from many people, I

wrote in a high school textbook about the massacres conducted by the Japanese

army in Malaysia. However through textbook screening, I was told not to write

about these matters. In the end, I was made to withdraw my manuscript about

this history.

I took this

matter to court, and took on the Minister of Education. I was able to claim

victory in the first district court, but in the later high court and Supreme

Court, I was forced into defeat by the government’s fallacious reasoning that

the court approved of.

|

| The first high school textbook with photos of a massacre memorial in Malaysia |

Still, this

picture of a memorial (in the textbook above) was submitted by another author, and was approved by the

textbook screening examiners. Now, both high school and middle school textbooks

are able to be published with these kinds of photographs.

There are many of you here who can read Chinese, or Chinese characters.

The biggest problem about my manuscript that was pointed out by the examiners,

was the use of the character “蝗”—locust. This character is a

combination of “皇” which is used to signify the emperor, and the character “虫” which means

“bug”. In this context, the said character is used as a substitute for “皇” in mentioning

the “皇軍”—the emperor’s army. Due to it being a homonym for “皇”, and its

fitting meaning of Locust—where they go, not a single plant is left—in Chinese

Malaysian newspapers it is often used to describe the wartime Japanese

military. I took a page of this newspaper article and put it in one of the

pages of my textbook, only for it to be rejected by the examiner. He could not

approve the profanity of associating a character meaning emperor with insects.

Upon having my manuscript rejected, I was faced with the reality that

Japan’s conservatives just cannot live with anything that discredits the

emperor in even the smallest way. This is why they also don’t like the idea of

war responsibility—because the Japanese army at the time was the emperor’s

army, which means the responsibility of the invasions will be put on the

emperor.

In the issue of Nanyang Siang Pau—the Chinese

Malaysian newspaper—which I showed previously, that stated how Japan’s

militarism still has not been done away with, there was a photograph of the

emperor. In addition to this, the textbook examiner from the ministry of

education said that he could not forgive the use of a character that discredits

the emperor. I feel that these two occurrences both speak to us of a problem

that Japan’s emperor system holds.

I feel that at the root of today’s historical

revisionism is the conservative sentiment of regarding the Emperor as an

absolute being, and this is also a large factor in maintaining Japan’s

militarism. While the people of Asia are extremely sensitive to signs of this,

the people of North America and Europe seem to be more or less indifferent. How

is it from your point of view? I would love to hear opinions.

Thank you for listening.

(End)

Thank you for this reminder. Yes, the hypervisibility of Pearl Harbor conceals the other sites of Japanese aggression and it does work for the U.S. to legitimize its claim to Hawaiʻi as "American territory" rather than an occupied country, and as you point out it sets up the U.S. as the only "liberator" and therefore the one with the right to claim the Pacific as the "American Lake".

ReplyDeleteIt is true that Pearl Harbour was not the only target that day. The reason for its emphasis is because it was an important US Pacific naval base. As a boy I remember my father told me

ReplyDeleteabout the attack and invasion of southern Thailand and Kota Bahru on the same day. I can't understand why there are still Japanese like Shinzo Abe who refuses to accept historical truth.

Satoko---your sharp reminder of the narrow mythologizing of the Pearl Harbor attack - and its current consequences -- is sooooo valuable!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Satoko, for making this speech available. I didn't know Kota Bharu was beginning to appear in history textbooks--what a good sign, when there are so few.

ReplyDeleteThanks to prof.Takashima's research in Malaysia, it becomes apparent that Japanese army selectively attacked and killed the Chinese residents and stimulated the hostility between Chinese and Malaysian. I have to realize again how brutal and cruel Japan had been against China and Chinese people and at the same time I myself have not understood the situation reported here in this research.

ReplyDeleteI have one point to point out. I think the historical revisionism of the Japanese government has far deeper root than the sentiment regarding the emperor as an absolute being. Japan had invaded the Korean peninsula in the 16th. century. The ultimate aim of the invasion was to possess China. At that time the emperor had not been an absolute being yet, so the aim had been of the ruling class as a whole. The ambition to possess China could have been survived for long time because of the geographical location and diplomatic isolation and the lack of diplomatic experience of Japan. For China Japan had been one of many neighboring countries, consequently China had shown no positive concern to Japan. But for Japan China had been the rival and the possessor of the land which only Japan had the capacity to control. When Japan was forced to have diplomatic relation with the U.S. and the European countries, Japan found the chance to carry out its life-long ambition.